If you’ve ever seen a cramped breaker panel, whether in a busy warehouse or a cramped laundry room, you’ve probably thought: “We’re out of space… can’t we just add a sub-panel?”It’s a fair question. Homeowners, property managers, and even warehouse operators hear this all the time. And on the surface, it sounds like a smart, budget-friendly solution. Why replace a full electrical service when you can bolt on more space and keep things moving, right?

Well… yes and no.

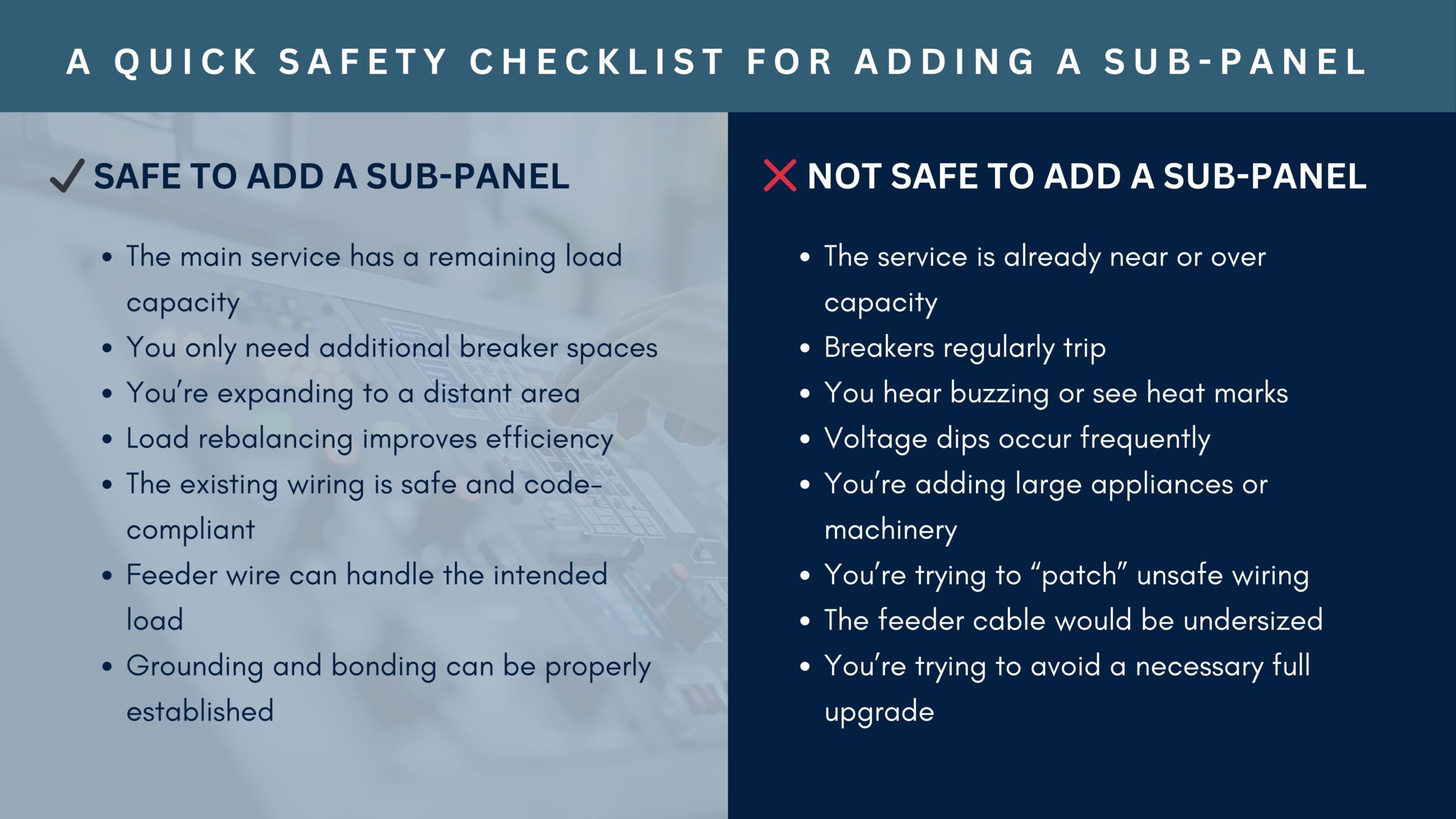

Adding a sub-panel can be completely safe, code-compliant, and incredibly helpful when it’s done under the right conditions. But in many commercial and residential environments, sub-panels are used as a shortcut. And shortcuts in electrical systems are a fire risk, a code violation, and in commercial settings, a shutdown waiting to happen. So let’s walk through when adding a sub-panel actually makes sense and when it turns into a reckless cost-saving gamble that comes back to bite you.

Understanding the Basics: What a Sub-Panel Is (and Isn’t)

A subpanel is a secondary electrical distribution panel that draws power from your main service panel, allowing you to add more circuits when the primary panel is full. Property owners often choose sub-panels because they’re less expensive than a full service upgrade, provide flexibility for new rooms or equipment, help organize electrical loads more efficiently, and reduce overcrowding inside the main panel. On their own, these reasons are perfectly valid. The problem arises when a sub-panel is added to a system where the main panel is already operating at or near its maximum capacity at that point, what seems like a practical solution can quickly become a serious safety risk. And this is where the trouble starts.

When Adding a Sub-Panel Is the Right Move

When Installing a Sub-Panel Becomes Reckless

Here’s the part most people underestimate, especially during renovations or budget crunches.

The Cost Pressure Problem: The Big Reason This Issue Keeps Coming Up

Electricians face this battle every week: “Why can’t you just add a sub-panel? We don’t want to spend money on an upgrade right now.” And while adding a sub-panel may seem cheaper in the moment, it often becomes far more expensive in the long run if the electrical system wasn’t designed to support it. In residential settings, homeowners want affordability, quick fixes, and the ability to run new appliances, EV chargers, hot tubs, or home offices without major rewiring. In commercial environments, the pressure comes from a different place, business owners want minimal downtime, fast expansion for new equipment or automation, and ways to reroute circuits without triggering utility shutdowns or inspections. The result is constant pressure on electricians to “just add a sub-panel.” But budget constraints don’t change electrical capacity, and neither the National Electrical Code nor the laws of physics make exceptions for convenience.

How to Tell If Adding a Sub-Panel Is Safe: A Quick Checklist

Commercial vs Residential: Why the Stakes Are Higher in Business Operations

While sub-panel mistakes are dangerous in any setting, the consequences are significantly higher in commercial environments. Businesses operate with high-current machinery, multiple simultaneous loads, and sensitive automation equipment that depends on stable power. Add OSHA compliance requirements, the risk of worker injury, mandatory insurance inspections, and the cost of downtime, and a single electrical miscalculation can ripple across an entire operation. In warehouses and production facilities, a poorly planned sub-panel can shut down conveyor lines, disrupt production quotas, or create hazardous arc-flash conditions that put employees at risk.

Residential systems carry a different set of risks. While homes typically operate with lower overall loads, they are far less forgiving when it comes to safety. Improper sub-panel installations can increase fire hazards, damage appliances, fail real-estate inspections, void insurance coverage, or compound the dangers of unsafe DIY modifications. In short, homes may tolerate less electrical demand, but when things go wrong, the consequences can still be severe, especially where life safety is concerned.

The Bottom Line: When in Doubt, Load Calculation Decides Everything

Electrical load calculation is not guesswork; it’s math, it’s NEC code, and it’s safety science. A qualified electrician evaluates total connected load, demand load, feeder sizing, service rating, voltage drop, and the difference between continuous and noncontinuous loads before approving any expansion. If those calculations indicate the system cannot safely support additional demand, adding a sub-panel becomes reckless, no matter how convenient or cost-effective it may seem. The simplest way to think about it is this: sub-panels are appropriate when you need more breaker space or better distribution, while service upgrades are necessary when you need more power. Confusing the two is where serious problems begin. Whether you’re expanding a warehouse, installing new machinery, or powering a home office without overloading circuits, the correct solution depends on an honest assessment of electrical capacity. When safety, uptime, and long-term reliability matter, choosing correctly isn’t optional.